With Overtime Expenses Piling Up, Nearly Half of East Lansing’s 20 Highest Paid Employees Last Year Were Police

Understaffing at the East Lansing Police Department is forcing officers to work long hours, bringing overtime expenses that are a weight on the city budget.

A Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request shows that last fiscal year, ELPD spent just over $700,000 on overtime and had spent more than $600,000 on overtime in the current fiscal year as of April 23. The fiscal year runs through the end of June.

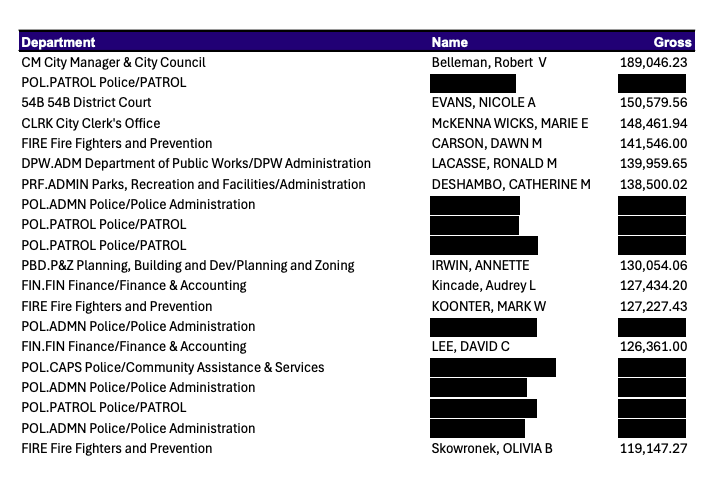

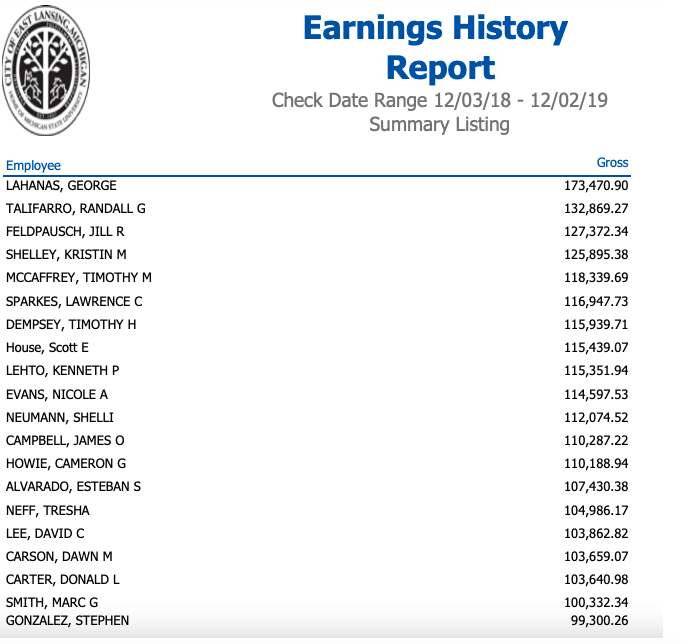

While we do not know the exact breakdown of how ELPD officers are being paid, we do know that ELPD employees are more represented among the city’s highest paid employees than in previous years.

Information obtained through another FOIA request shows that nine of the city’s 20 highest paid employees in 2024 came from within the police department. When ELi looked into the city’s 20 highest paid employees in 2019, five worked in the police department. In 2022, that number grew to seven.

Unlike in past years when the names and gross pay of East Lansing’s highest paid employees were provided when requested, the city decided to redact the names and wages of police department employees, citing a FOIA exemption that allows police personnel information to be kept hidden.

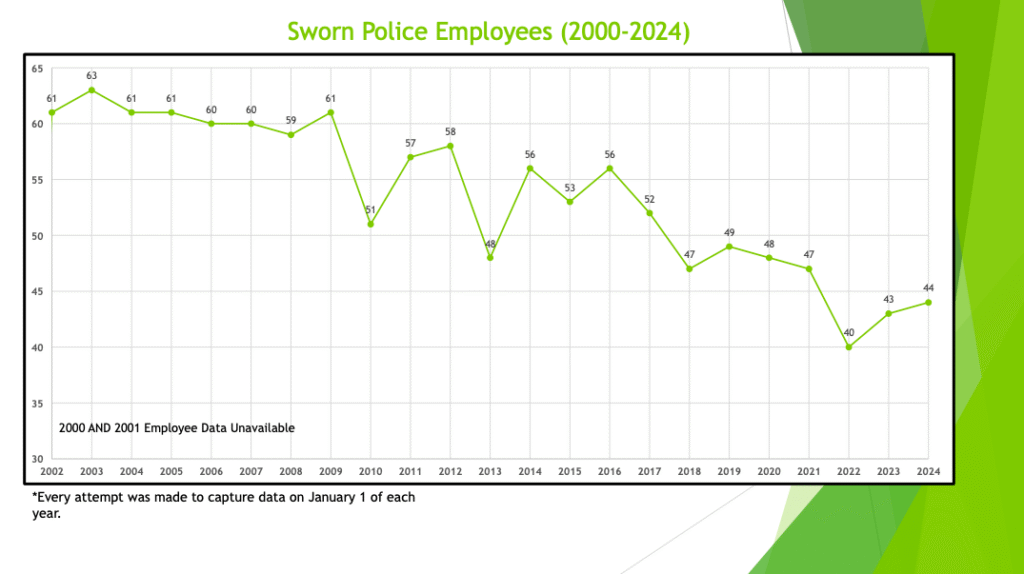

ELPD has significantly fewer officers than it used to.

Perhaps the biggest contributing factor to the overtime costs is the sharp decline in officers that ELPD has on staff. According to a graph attached to a recent City Council meeting agenda, since 2000 ELPD peaked with 63 sworn officers in 2003. Currently, the city has 44 sworn officers and is budgeted to employ seven more. When the fiscal year concludes at the end of June, it will mark the sixth consecutive cycle that has passed with ELPD not reaching full staffing.

With fewer officers responding to calls in East Lansing, ELPD leaders and other city officials have said that officers are scrambling to keep up with the call volume.

One of the consequences of low staffing that is frequently discussed at city meetings is that the ELPD road patrol is at three officers most times, when it would be at five if ELPD were fully staffed. This means fewer officers are patrolling the streets to enforce traffic laws.

The city cut its workforce in the 2000s as it came to grips with its pension debt crisis, but ELPD’s problem isn’t just that it is budgeted to employ fewer officers. The department has been unable to fill the positions it does have funding for.

Right now, ELPD has seven vacant officer positions. Police Chief Jen Brown recently said at a budget session that the police department has commitments to fill these vacancies, but it takes time for those commitments to become boots on the ground.

Brown explained that most of the recruits will graduate from the police academy in December, and then will go through several months of internal training before they are ready to handle regular responsibilities. The whole process of turning committed recruits to full-time officers can take upwards of a year. During that time, some ELPD officers may retire or leave for a different job, creating more vacancies.

To speed up the hiring process, ELPD can make a “lateral hire,” and find an experienced officer looking for a change of scenery. This officer would not need to go back through the police academy, and would receive an expedited in-house training at ELPD. Recently, ELPD posted on its Facebook account encouraging officers with experience to apply to work at ELPD.

The ever-present challenge ELPD faces is competition from nearby entities like Meridian Township and Michigan State University that may lure employees away from ELPD or steal commitments from recruits.

Overtime wages will be an ongoing cost due to pensions.

The staffing vacancies that make overtime necessary are somewhat softened by short term savings on staffing costs. At the May 13 City Council meeting, City Manager Robert Belleman said a new police officer costs about $94,000 per year, when accounting for salary and benefits. Those savings, however, dissipate when considering the impact overtime can have on officers’ pensions.

Perhaps the biggest anchor on the city’s financial outlook is its unfunded pension liability. While the city has been making gains on paying down its pension debt in recent years, it still allocates a significant chunk of funds to the plan every year. Most notably, 60% of the net revenue generated by the city’s income tax goes to paying down the pension liability each year.

As the city came to grips with its pension debt crisis, it substantially cut its workforce across many departments, not just ELPD. While the city also changed many of its pension plans to be less costly for the city, in a February interview about local finances, Belleman explained that some of the veteran police officers are still on plans that base their pension on the rate of pay during their three highest paying years of service, including overtime.

“I saw some that were 40, 50 thousand dollars a year in overtime,” Belleman said in the February interview. “That’ll have an adverse impact on your pension when you go to retire because then their monthly pension payment will be adjusted to meet what is considered their final average compensation.”

The city is looking for new ways to fund police overtime.

Along with the staff vacancies, East Lansing’s existence as a college town will naturally bring a need for police officers – as sports games and other large university events will routinely bring temporary influxes to the city’s population.

The budget for next year, which City Council will adopt Tuesday, May 27, is expected to include a $200,000 contribution from the Downtown Development Authority (DDA) to help pay for overtime expenses racked up in the downtown area.

City officials have even floated the idea of installing a fee structure that would charge downtown businesses that call the police. The proposed fee structure would bill downtown business owners for overtime expenses after the $200,000 committed by the DDA is spent.

The charge for service would be applied on “busy nights,” described as Thursday through Saturday nights, Saint Patrick’s Day, athletic tournaments in the city and bar crawls.

When the idea was discussed, some council members worried the structure could discourage business owners from calling the police and is unfair. However, there was some interest in adopting the fee structure. One council member said it makes sense to have businesses that call the police more frequently pay extra.

“If I have more trash than fits in my trash can, I pay a fee. If I have a bulk item for pickup, I pay a fee,” Councilmember Erik Altmann said of the fee structure at the March 7 council meeting. “This mix of taxes and then fees for dedicated services is nothing new and it helps keep it fair. So, I think the structure here is just fine.”

Working long hours is taxing on officers.

In a conversation with ELi, Brown praised ELPD officers’ for their willingness to take on extra hours.

“Even when they may be tired or have already worked their 40 or 50-plus hours, they are always willing to help out,” she said. “That really sets them apart from the other department that I worked at, as well as in the private sector.”

Still, the police chief acknowledges that taking on too many extra shifts will take a physical toll on officers eventually.

“It’s hard,” she said. “You work all that overtime and at some point it has to take a toll. Whether that’s your sleep, or your nutrition, or your exercise – something has to go when you’re working that many hours.”

Brown added that ELPD has put extra focus on officer wellness recently, even bringing in speakers to talk to officers about things like nutrition and mental health.