You’re Never Over It: Parents of Children Lost to Suicide Discuss Grief

Call or text 988 to reach the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, or visit 988lifeline.org for chat support and resources if you or someone you know is struggling. Help is always available.

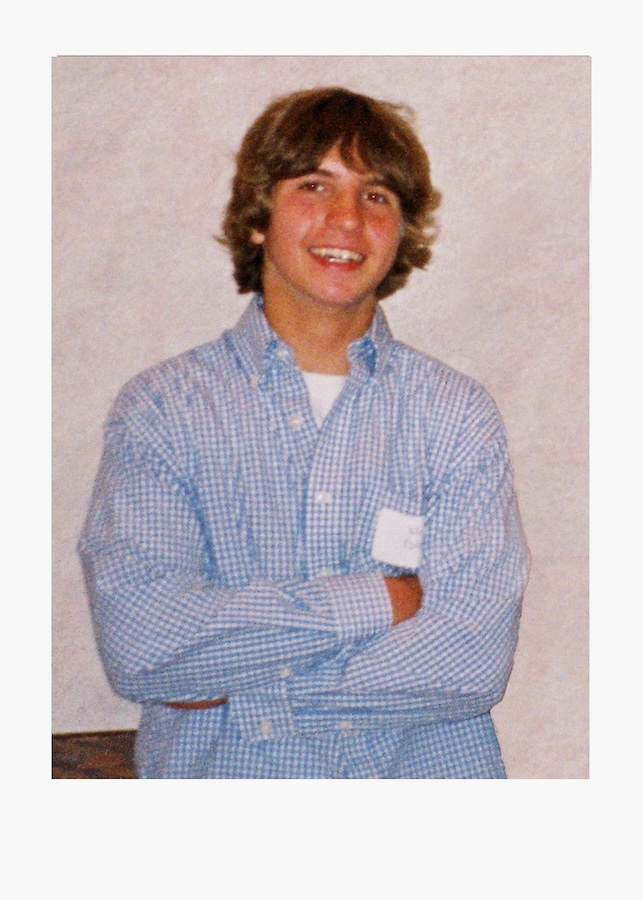

“He lived large until he couldn’t anymore.”

That was how Eli Fleetwood’s 2022 obituary began. The 15-year-old is one of several East Lansing-area youth who have been lost to suicide in recent years.

For the last two decades, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported that suicide remains the second- or third-leading cause of death among U.S. teenagers. In Michigan, the Department of Health and Human Services recorded 11.2 suicides per 100,000 people between 2013 and 2022.

Beyond statistics, young people who end their lives leave behind parents and families who will spend lifetimes searching for answers that will not come.

Beth Stuever brought Eli and his two sisters home when he was three and a half years old. She and her ex-husband had signed up to be foster parents and said they were interested in sibling groups—never imagining three children would need them.

Two of the siblings were undernourished, and Eli’s vocabulary was stunted. But he was ready for a family, Stuever said. She recalled the day he came to live with them.

“Eli kind of got out [of the car] and looked around and said, ‘I want to go into that house,’” she said. “Luckily, he pointed at our house. He was just ready to go in and see what was going on. He asked a lot of questions and wanted to know where the backyard was. He’s always been a very curious kid.”

Eli faced addiction issues that he inherited from his birth parents, Stuever said. It was one of several complications he carried from the family he started life with.

“They uncovered very quickly that Eli had [Attention Deficit Disorder] with hyperactivity, which isn’t a huge deal,” she said, recalling his evaluation at the Children’s Trauma Assessment Center. “But that’s when we also found out that Eli had [Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder]. I thought you had to go to war to have PTSD, but he had witnessed domestic violence in the home [he spent the first three years of his life in].”

While the diagnosis surprised her, it also made sense of Eli’s behavior. When the family encountered police officers or members of the local fire department, Eli would tell them they had to hide because “police take parents away.”

Eli first attempted suicide in seventh grade. Stuever heard her youngest child upstairs yelling before coming down to say that Eli was in the closet and wouldn’t answer.

“I went upstairs and he was hanging in the closet with his back to the room,” Stuever recalled. “He had a belt around his neck and he was passed out.”

She brought her son to the floor and yelled to her then-husband, who came and performed CPR, while her older daughter brought her a phone so she could call 911.

“It turns out they were there in eight minutes, but it seemed like hours,” Stuever said. “He was still passed out when they took him to the hospital.”

Eli woke up in the NICU, where he stayed for two weeks before spending another two weeks in a psychiatric hospital.

When asked if Eli ever told her what he was feeling when he attempted suicide, Stuever paused.

“He couldn’t put it into words,” she said. “When Eli was off, there were signs that we could see. If he was walking and wasn’t swinging his arms but his arms were really stiff, we’d know something was going on. That weird chemical imbalance is something that’s hard to figure out.”

Eli ran away in June 2022 as Stuever was preparing to leave for a work conference. He had run away before but always returned after blowing off some steam, she said.

“All of a sudden, there were seven people in my front yard,” she said. “I don’t know why I remember the number. Two just regular cars and at least one cop car parked out by the road. I opened the door and said, ‘Did you find Eli?’ thinking that he had run away and they had arrested him for something.

“And that’s when they told me that they did, and I remember being really confused because the woman who gave me the news said, ‘We did find Eli and I’m sorry, but he didn’t make it.’ And I didn’t know what she meant. They told me he was deceased. And I hate that word.”

Eli died when he was 15. Some of his friends and a teacher decided to throw a 16th birthday party for those he left behind.

“The teacher friend said to me that they thought it would be good for everyone and give them some closure,” she said. “I know she meant well, but I will never have closure. I’m going to celebrate every birthday, including his 18th next month.

“It’s a long process—a process that never ends. It just changes over time. Don’t think you have to bury those feelings.”

Kevin Epling said his son Matt was energetic and outgoing, the kind of kid who liked being the center of attention.

“When he was finishing seventh grade, he had been voted by his classmates as class comedian and most likely to succeed,” Epling said. “He was a good kid and had a lot of friends. I called him one of those linchpin kids because everybody knew him and he was able to bring people together.”

Despite his popularity, Matt was attacked by three upperclassmen on the last day of his eighth-grade year in spring 2002. They smashed eggs on him, pushed him against the running engine of a car with its hood up, and threw his bike into a sewage drain.

“Police came and said that it’s an assault and battery,” his father remembered. “It’s not just bullying—it’s assault and battery.”

The harassment didn’t stop there. The boys came to Meijer, where Matt worked, and started bothering him again.

“The night before we were going to go and talk with police and file charges [against them],” Epling said, “Matt took his own life.

“It was never anything in my mind, or my wife’s, that he would harm himself.

“The impact of someone taking their life is just beyond comprehension,” Epling said. “It’s the worst thing that could happen to you, and that’s not even probably on your list. It’s very, very difficult to prepare for something like that that’s out of the blue.”

Epling said that when someone dies by suicide, others often assume there’s something wrong with the family, or they stay away.

“Suicide loss is so different than any other loss,” he said. “If it’s a cancer loss, people rally around those families—they’re fighting, they’re fighting. If it’s a drug overdose, people say, ‘Oh, they didn’t know what they were doing.’”

It’s important for people outside a family’s grief journey to understand that the journey is necessary—and individual, Epling said.

“Trying to explain and tell someone how you think they should do it doesn’t really work,” he said. “We’re all different, and I think it’s important to give people the time and leeway they need.

“One day you can be perfectly fine and the next day, you see something, hear something, and you kind of have a grief burst. Give them the room to grieve in the way they need to… but don’t let them get stuck.”

Heather Martin would probably agree that she almost got stuck after her daughter Sydney Zaban died by suicide in January 2016.

“I literally referred to her as the baby that changed my life,” she said. “She was the person who changed everything about my life. I looked at her like she was a miracle. For me, it was evidence that miracles did exist, because here I was—somebody that never wanted children.

“The main goal of my whole parenting experience was that my child would never question the love I had for her, which made what happened even more devastating.”

Martin described a daughter she not only loved but respected, and in whom she placed her hopes.

“She was very caring about other people,” she said. “I’m talking about all people. If we drove by a homeless person, she would be like, ‘Can we give him something? Can we go buy him food?’ At one point, she told me that she could see other people’s feelings.”

Sydney was struggling in her Lansing school. Martin said she had been diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum and was easily distracted by noise.

“They told me that I should probably have her go to a different school,” Martin said. Sydney was granted admission to East Lansing schools as a school of choice student.

Martin said Sydney had intentionally cut herself about two years before she died.

“We discussed it, and she made it seem like it wasn’t a big deal. She said she would never do it again, and I never saw evidence of that again,” Martin said. “My daughter was in therapy the entire time. I was trying to do all the things you’re supposed to do as a parent when you feel your child might be struggling.”

Martin didn’t learn about some of Sydney’s pain until after her daughter’s death.

“That’s why when parents say that their kid would never do that, I literally cannot help myself,” she said. “I roll my eyes and think that they have no idea. You truly have no idea, because I was that parent. I did have a close relationship with her. I really did. But I was blindsided.

“She would have made an absolutely wonderful adult. She would have made a wonderful mom. And she would have made a wonderful daughter to me as I aged. I miss her all the time. And I tell people, watch your friends—don’t leave them alone. Because they’re not going to tell you. They’re not going to tell you what they’re thinking.”

Each individual grieves uniquely and may not conform to others’ expectations for what a grieving parent should look like, Lansing-area social worker Chloe Silm told East Lansing Info.

“For a parent experiencing the death of a child, there’s probably every hard emotion you can feel mixed in there together,” she said. “With a suicide death, it can be even more difficult. You have so many unanswered questions—questioning yourself, your parenting, even the world. And the hard part is, most of the time, you’re not going to get answers. Finding peace means accepting that some questions will remain unanswered.”

Silm is a social worker at Ele’s Place in Lansing, a nonprofit organization that helps people struggling with grief after the death of a loved one. She said that connection, like what Stuever has found with other parents impacted by suicide, is vital in healing.

“Support groups are one of the most healing things you can do,” she said. “There’s something about being with others who truly understand your pain. You don’t have to explain yourself.”

Silm added that families grieving a suicide loss often deal with complex emotions, including guilt, anger and confusion.

“I remind parents that grief isn’t linear,” she said. “You don’t go through neat, tidy stages and come out the other side. It’s more like waves—sometimes small, sometimes overwhelming.”

And one of the hardest things to navigate for parents is learning to live with those waves, Silm added.

“You don’t get over it,” she said. “You learn to live with it. The goal isn’t to stop grieving—it’s to find ways to carry that grief while still living your life.”

Stuever remembers Matt’s dad coming to Eli’s funeral. The two had never been super close, but they both worked at Michigan State University in similar areas. She found Epling looking at pictures of Eli.

“He said, ‘I see an athlete and an artist,’” Stuever remembered. “He’d never met Eli but what he saw of Eli in the pictures, he described what he saw perfectly. And then he said to let him know when I was ready.

“That was the best thing anybody could have ever said in that moment because so many people want to know what they can do to help you. And you don’t know what you need,” Stuever said. “And for Kevin just to say, ‘Let me know when you’re ready,’ that was helpful.”

She said that she runs into people and finds a common bond with those who have lost a child. She recalled meeting someone at Van Atta’s the week before and they found out they both lost a child and instantly bonded.

“I think we do kind of need to stick together,” she said.

“If a child tells you that they have suicidal ideation, listen but don’t freak out,” she said when asked what she would tell other parents. “Talk to them about what some options are and get them help. Stay with them. Don’t be afraid to take your kid to the emergency room or a psychiatric hospital. Eli’s time in psychiatric hospitals really helped stabilize him for a long time.

“Make sure your kids know that there’s nothing to fear.”